|

Table of Contents

|

| "On Baptism during a Pandemic" :

PDF Download |

To put it most simply, the power, effect, benefit, fruit, and purpose of Baptism is to save. No one is baptized in order to become a prince, but as the words say, to “be saved.” To be saved, we know, is nothing else than to be delivered from sin, death, and the devil and to enter into the kingdom of Christ and live with him forever. –Martin Luther1

I am a child of the Cold War. The Berlin Wall did not fall until I was a junior seminarian. Atomic Armageddon was not just the stuff of movies; it was something we talked about. Indeed, I gave a presentation in my high school nuclear science class on how to build a bomb shelter on short notice. The danger was real, and declassified American and Soviet documents have revealed that we came closer than we could have imagined to a last day of our own making . . . more than once. Despite that threat, the vast majority of us could go about our quotidian business without much modification. We went to school, learned to drive, and danced at the prom. Even if there was some existential dread, its intrusion upon our consciousness was relatively limited.

A pandemic is different by nature. The threat of death is experienced more individually, especially given the way some die and others do not. It is also more personal in that we know (or, at least, know of) people who die, and we can have a very personal brush with death should we become sick. It is also more present. Mutual Assured Destruction hung above us like the Sword of Damocles, but a pandemic walks by our side, sits at table with us, and crouches by the door even when we bar it. A pandemic intrudes upon our consciousness, and, for good reason, we make adjustments to the way we live.

Church life, like home, civic, and work life, has been no exception when it comes to making adjustments. Different congregations (and individuals) have made different adjustments, but no one can say that there hasn’t been any change even if the change has been nothing more than some members choosing to absent themselves from the gathered assembly. Among the many matters related to worship, questions about Eucharistic practice have been legion, and not all the answers proffered have been meet, right, or salutary. Even so, one cannot fault the desire to address these questions, even if such desire proved insufficient to guarantee appropriate action. One also cannot fault the amount of energy and time devoted to these questions, evidence of the importance of Eucharistic celebration among us.

The purpose of this missive on this day, The Feast of the Baptism of Our Lord, is not, however, to rehash Eucharistic questions. I mention them as example of where the clergy and laity of the church, in the midst of an unusual situation, identified an important issue and attempted to address it. I mention them also to highlight, by contrast, questions which have not occupied us, namely, questions about baptism during a pandemic. Indeed, public conversations about the importance of baptism and appropriate baptismal practice in the midst of the same conditions that have so challenged our Eucharistic practice have been but a fraction of the sacramental debate, and a tiny fraction at that.

I could hope that the scant attention given to baptism at this time is evidence that we know what we are doing with baptism. I have had enough conversations, however, to identify some areas of concern, and I will attempt to address them in this document. Before doing so, let me suggest that our scant attention to baptism may be a function of its rarity among us. What do I mean? Well, we tend to focus on those things that we do all the time. For many of our congregations, the Eucharist is weekly. For the rest, with some rare exceptions, it is, at least, monthly. Of course, we are going to spend time worrying about the Eucharist because it is routine (and I do not mean that in a bad way). Baptisms are not nearly as common. Sadly, some of our congregations have gone years without a baptism. From a very practical perspective, why spend time worrying about something that is not on the schedule for next week?

|

If the threat of the pandemic is

death, shouldn’t we be thinking about the sacrament

that, in Luther’s words, delivers from sin, death, and

the devil?

|

There is good reason to think about baptism. Indeed, it is always a good time to think about baptism but even more so in the midst of a pandemic. If the threat of the pandemic is death, shouldn’t we be thinking about the sacrament that, in Luther’s words, delivers from sin, death, and the devil? If a secondary threat of the pandemic is the loss of charity for our neighbor, the increase in selfishness, and the giving of oneself over to anxiety, shouldn’t we be thinking about the sacrament that, in Luther’s words, delivers from sin, death, and the devil? If the one who prowls around like a roaring lion will use all these things in his attempt to devour us, shouldn’t we be thinking about the sacrament that, in Luther’s words, delivers from sin, death, and the devil? The “power, effect, benefits, fruit, and purpose of Baptism is to save.” What greater lifeline has Christ thrown to those who face death? What greater shield and buckler has Christ placed upon the arms of those assaulted by the devil? What greater sword has Christ put in the hands of those called to slay sin? Surely this should be reason enough to think about Baptism, as it offers so much good in a time so desperate for something good. It should also be reason to extend the offer of baptism—or shall we say, “extend the promise that Christ offers us in baptism”—with greater liberality than has been our custom. Having received this seal of God’s gracious promise, a miserly hoarding of that inexhaustible grace is inconsistent with Christian charity.

Another reason to think about baptism is preparedness. That baptisms are not as frequent in our congregations as the mass is no reason to assume that we will not be called upon to baptize. If we are to administer this sacrament—and we are—then we should think about how we are going to administer it under pandemical conditions. We might also consider that baptisms of both adults and children could become more common were we actually to commend and recommend baptism, and let us not forget the possibility of emergency baptism for those in periculo mortis (danger of death).

As I have suggested, with respect to sacraments, we turned our attention to questions related to Eucharist practice in a pandemic because those questions seemed more urgent. Taking a step back and thinking about the relationship between the sacraments, as outlined in our Confessions, questions of baptism in a pandemic take priority for three reasons: 1) baptism is sacramentally prior to the Eucharist; 2) even when we cannot receive the Eucharist, we can still lean upon the promises of baptism; and 3) necessity is ascribed to baptism in the Augsburg Confession. By itself, this last point, necessity, is sufficient to not only make baptism a topic of our deliberations but to also give it priority over those matters not defined as necessary. To the second point, many, without benefit of viaticum,2 have died in a sure and certain hope that, having been united with him in a death like his, they shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. To the first point, baptism is the external and visible means by which we become members of the church visible and, in faith, the church invisible while “the Lord’s Supper is given as a daily food and sustenance”3 given to those who have been baptized.

|

...the necessity ascribed to

baptism, as well as its surpassing appropriateness

during a pandemic, should compel us to baptize with

even greater urgency.

|

An objection might be raised that it is too late to think about baptism in a pandemic. It would be too late if the pandemic were behind us. It is not, and we do not know when we will return to our customary practices. It is likely that mitigations will continue in one form or another and that those mitigations shall loosen and tighten repeatedly in response to the situation on the ground. Consequently, there may be constraints (even if self-imposed) upon our actions related to baptism. These constraints, however, should not preclude Baptism, and the necessity ascribed to baptism, as well as its surpassing appropriateness during a pandemic, should compel us to baptize with even greater urgency. Returning to classical Lutheran categories, we know that we cannot abandon Baptism itself, as it is an essential, nor can we modify those material and formal causes4 of the Sacrament that are also essentials. Our questions related to practice, therefore, are within the realm of adiaphora (non-essentials). First, we must distinguish between essentials and adiaphora, and, second, we must consider the best regulation of adiaphora under the current conditions.

The essentials of baptism, so far as the rite is concerned, are minimal. There is water, and there is a particular Word accompanied by the administration of the water. Something which is not water may not be employed in place of water. The water, however, can be tap water, water purchased at a store, water taken from the local well, etc.. Remembering this is especially useful in an emergency. I have grabbed a bottle of sterilized water off the shelf in a PICU room to perform a baptism as the helicopter crew entered. I did not need a vial of water from the River Jordan to administer a valid baptism, and, to not have baptized for lack of such a vial, under those circumstances, would have been pastoral malpractice.

As for the Word, the Trinitarian formula (“in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” or “in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit”) is to be used without modification. The Trinitarian formula is introduced with either “I baptize you…” or “_____ is baptized….” These words are to be accompanied by the administration of the water. While copious amounts of water are to be preferred, some situations may call for very little, e.g., a friend told me of using a medicine dropper in a NICU because of the constraints associated with the setting. Again, this is important to remember in an emergency, when there may not be time for extensive prayers or other liturgical elements and practices.

One might ask: What about the exorcism, chrismation, the candle, etc.? All these things are good and, when possible, should be included, but emergency conditions (or other constraints) may militate against their employment. Here, we might remember Luther's comment, in his “To All Christian Readers,” what became the preface of his Order for Baptism in German (1523),

Now remember, too, that in baptism the external things are the least important, such as blowing under the eyes, signing with the cross, putting salt into the mouth, putting spittle and clay into the ears and nose, anointing the breast and shoulders with oil, christening robe, placing the burning candle in the hand, and whatever else has been added by man to embellish baptism. For most assuredly baptism can be performed without all these, and they are not the sort of devices and practices from which the devil shrinks or flees. He sneers at greater things than these! Here is the place for real earnestness.5

A brief comment: while the water, its administration, and the Word are external things, they are not in the same class as those things Luther here enumerates as externals, as the things Luther here enumerates are not of the essentials of baptism. They are, as Luther puts it, embellishments. There is nothing wrong with embellishments so long as they support that which is essential (or, at least, do not detract from that which is essential), but they are, in themselves, unnecessary, allowing us to dispense with them in those instances when they detract from or prevent us from doing what is necessary.

|

We do not baptize the dead, nor do

we baptize by proxy.

|

Of course, having the actual baptismal candidate at hand is indispensable. We are baptizing somebody, and that somebody has to be present. We do not baptize the dead, nor do we baptize by proxy. By the same token, the one baptizing has to be physically present to the one being baptized. A question about Zoom-baptism was raised early in the pandemic, and my response to that is posted on the web.6 While there is such a thing as a baptismal emergency, there is no circumstance that justifies a pastor Zooming in and attempting to baptize remotely. Were the pastor not available and an emergency arose (threat of immediate death), then one of those present (a lay person if there is no pastor present) should baptize. Some might say that baptism by Zoom is just as valid, but such claims ignore the indexical7 nature of sacramental language. Besides, there is no reason to introduce a dubious practice when sound practice is available. Arguments favoring dubious practice that are proffered to fulfill sentimental or co-dependent ends should be dismissed because such ends are alien to considerations of validity.

With respect to adiaphora, we must always remember that indifferent does not mean unimportant. At the same time, important does not mean indispensable. For those unfamiliar with the concept of adiaphora, let me say, briefly, that an adiaphoron (singular) is something that is a matter of indifference with respect to the Gospel (and the Law), i.e., it is neither commended nor prohibited by God. In sixteenth-century usage, it usually refers to ecclesiastical practices connected with worship. I refer you to the Article X of the Solid Declaration of the Book of Concord for the Confessional rendering of the subject.8 By way of example, the amount of water used in baptism is an adiaphoron. Whether by immersion (dunking) or affusion (pouring),9 baptism is valid. That said, Luther writes, in The Babylonian Captivity of the Church (1520),

It is therefore indeed correct to say that baptism is a washing away of sins, but the expression is too mild and weak to bring out the full significance of baptism, which is rather a symbol of death and resurrection. For this reason I would have those who are to be baptized completely immersed in the water, as the word says and as the mystery indicates. Not because I deem this necessary, but because it would be well to give to a thing so perfect and complete a sign that is also complete and perfect.10

|

...it would be ridiculous to

withhold baptism from a dying person because there is

no swimming pool readily available.

|

Here we see the careful balancing of essential and adiaphora. Luther prefers immersion but not for any essential reason. His rationale is pedagogical. Immersion would more clearly teach significance of baptism to the one baptized and to those witnessing. It is as if the method of baptism is a visual aid. Luther thinks it better to immerse in order to teach, but he does not deny the validity of baptism by affusion. We might say that not all adiaphora are created equal. Some are better. Some are worse. When possible, one opts for that adiaphoron that is better. Indeed, one may go to great lengths to secure the better adiaphoron. Sometimes, however, it is not reasonable to choose the better adiaphoron. In those cases, so long as the essentials are maintained, one should not withhold that which is necessary. Luther may have preferred full immersion, but it would be ridiculous to withhold baptism from a dying person because there is no swimming pool readily available. In less extreme cases, we might struggle more to draw the line. A thorough treatment of the exercise of prudential discretion in less extreme cases is beyond the scope of this paper, but those interested in such an exploration might begin by examining the twin-concept of economia (οἰκονομία) and akribia (ἀκρίβεια) in canon law and ecclesiastical practice.

With the aforementioned in mind, let us think through areas where

confusion about adiaphora has become a problem. Some of the

examples are primarily areas related to the clergy. Others are

primarily related to the laity. Before embarking on specific

examples, I want to be clear that most of the confusion is rooted

in a well-intentioned desire to do that which is better in terms

of adiaphora. Luther, as demonstrated, attempted reform of baptism

with this in mind, and he was preceded in this by some German

Roman Catholic bishops. Gerberding, in The Lutheran Pastor

(1902), offers a series of recommendations related to the reform

of baptismal practice in the American context. Martin Marty’s

little book, Baptism (1962), concludes with his

suggestions for baptismal practice, many of which have become the

norm. Philip Pfatteicher’s recommendations in the Manual on

the Liturgy—Lutheran Book of Worship (1979) continued this

movement—this work should be on every Lutheran pastor’s shelf.

These three works, along with rubrics found in numerous worship

books and minster's agendas going back well into the nineteenth

century, demonstrate a desire among educators and liturgists to

inculcate what was believed to be a better and, sometimes,

corrective baptismal practice. The inherent problem in teaching

good practice for normal times is the tendency to overlook what

might constitute good practice in abnormal times. They are not

always identical, and it is all too easy to treat adiaphora as if

they were essentials. So, in no way wishing to undo the work of

more than a century, I wish to explore certain adiaphora in

relationship to the current conditions, remembering four things:

1) we are still in a pandemic; 2) we don’t know when the pandemic

will end; 3) adiaphora suited for the pandemic should not become a

new default setting; and 4) we may see another pandemic in our

lifetime.

No. It is good to perform baptisms during the principal worship service for many reasons, but it is not indispensable. Under normal conditions, it is to be preferred and, with few exceptions, should be the norm. That said, limitations upon the principal worship service may militate against baptism being administered in that context. Congregational worship was suspended in most places for several weeks, even months. When in-person worship recommenced, many congregations adopted limitations upon capacity and/or length of service. These and other constraints come and go even to this day and may be expected to come and go for the foreseeable future. As baptism is necessary and, in the midst of a pandemic, of surpassing value, it should not be withheld because such constraints make its administration during the principal worship service of the congregation unreasonable.

Older rubrics allowed for the appointment of a special service for baptism.11 That may still not resolve the issue. As a last resort, a private baptism should be held. If, because there are constraints upon baptizing at the principal worship service (or other service of the congregation), the choice is between a private baptism, something that is not to be preferred in normal times, and no baptism at all, the choice should be to baptize privately. This assumes that the reason for choosing the private baptism is, in fact, related to pandemical constraints upon the worship services of the congregation. We would not want to see the return of private baptisms as the norm, so this should be considered a dispensation from normative practice because of unusual conditions.

The objection may be raised that once private baptisms are allowed, all the work accomplished to bring baptism into the regular worship service of the church will be undone. Indeed that is a risk, but what is that risk in comparison to the risk of death without the benefit of baptism during a pandemic? Clear and explicit teaching about the balancing of adiaphora under different conditions is in order and may prove helpful. This can be done in, e.g., in a newsletter article or even a sermon in which the private baptism is announced. Instruction may include a setting forth of the benefits of and rationale for public baptism with the understanding that such is not always possible.

Though somewhat tangential, this question may also benefit from thoughtful consideration of adiaphora. It is certainly a great joy and blessing to have a baptism at the Easter Vigil. It should be remembered that the historic practice of baptism at the Easter Vigil was associated principally with adults (or, at least, non-infants). Lent should not be considered a “closed season” with respect to the baptism of infants and young children. The benefits of a baptism at the Easter Vigil do not outweigh the risk of an infant dying as the weeks tick by. The Lutheran dogmatic tradition can tolerate an adult or older child going through a catechumenate prior to baptism because faith among such is usually present prior to the baptism as a consequence of the preached/taught Word. In the case of infants, baptism is the medium by which faith is first conferred and sealed.12

Hospitalization, depending upon the reason for the hospitalization, may suggest administration of baptism in that setting, especially if the candidate is in periculo mortis. This has been complicated by visitation restrictions. The most extreme restrictions have prevented all visitors. More common is the limitation of visitors to the point that the pastor may not be admitted. Larger hospitals have staff chaplains. If there is reason to baptize while the candidate is hospitalized, a request should be made that the staff chaplain baptize. It would be wise to confirm with the staff chaplain that the baptism will be conducted according to Lutheran norms for material and formal causes. Be sure to secure certification that the baptism has been administered. If the hospital does not have a staff chaplain, and there is danger of death, impress upon the appropriate authority the importance of this rite, remembering that in periculo mortis, a lay person may administer if a pastor is prevented. Usually, the patient, MPOA, or next of kin, by making a direct request to the hospital staff, will have more success in securing the pastor’s access to the patient than the pastor will have.

Baptize. What else needs to be said? Why would we deprive the comfort of baptism to someone in hospice? All that could be said about the hospital setting may be said here.

This is a reasonable concern, but it is also a concern that must be held in balance. It might be better for the hospital chaplain to baptize the child before it leaves the hospital than to wait an indefinite amount of time after the child arrives at home. A private baptism is less exposure than a baptism in a congregational worship service. Still, some may worry about the pastor even coming into the home. Masking, vaccination, etc., if it puts the pastor in the same risk category as others that come in and out of the house, should be sufficient. If it is not deemed sufficient, there is much that can be done to modify the administration such that the essentials are preserved while adapting to the circumstances. The rite for emergency baptism may be used to limit time. The baptism could be administered outside. The pastor does not need to make physical contact with the child, using a baptismal shell or similar device (but, for the sake of decorum, not a squirt gun—so help me, if I see that meme one more time…).

First off, it should be remembered that the sponsor in the baptism of an infant or young child is the one that has and can discharge direct responsibility for raising the child in the faith. In most cases, this is the parent. Increasingly, it is a grandparent or some other relative that has taken custody of the child. Those that are said to sponsor but are not expected to actually discharge the associated duties (such as the classic “godparent”) are symbolic. Relatives and friends are also cherished attendees at baptisms. Symbolic sponsors, godparents, and even friends and relatives are not essentials of baptism. It would be better to baptize and hold an anniversary party at some later date than to delay because beloved others cannot be present. By comparison, I have counseled military couples to marry prior to deployment, even if not everyone can be present for the wedding because a spouse has a standing, should there be an injury or, worse, death, that a fiancée does not. That doesn’t sit well with some, but it is a clear-eyed approach to the situation. It seems to me that the stakes are greater in the matter of baptism, calling for an equally clear-eyed approach with respect to dangers and benefits over and against sentimental preferences.

Masking and gloving (or using a shell or similar device) does not interfere with the validity of baptism’s material and formal causes. It is not necessary that the pastor hold the child. All that said, a pastor carefully administering baptism poses less danger than a grandparent picking up the child and kissing it. Likewise, if there are already members of the family (or others) going in and out of the house, a pastor poses no greater danger, assuming appropriate mitigations. Even so, if warranted by conditions, the rite for emergency baptism can be used. This will reduce the time required while preserving the essentials. If the rite for emergency baptism is used, the rite for public recognition of a baptism should then be used when it is possible to do so within the context of the regular worship of the congregation. The rite for public recognition should not be used if the non-emergency baptismal rite has been used. If emergency baptism has been administered to an adult and the emergency has passed without death, it seems better to invite the adult to undergo the rite of confirmation when possible. As previously stated, baptism can be administered outdoors.

It would be good to teach the people from time to time, as opportunity arises, on the “why,” “when,” and “how” of emergency baptism. Expecting parents should be instructed in this. The general rubrics associated with the baptismal rite in the in the Lutheran Book of Worship (1978) state, “The baptism of infants and young children should be arranged well in advance so that adequate time is allowed for the pastor to discuss the meaning and significance of the event with the parents and sponsors.” If this rubric is to be followed without losing the urgency that is Confessionally and dogmatically appropriate with respect to the baptism of infants and young children, then pre-baptismal instruction should begin during pregnancy and, then, early enough in the pregnancy so as to be of help should there be a premature delivery.

This instruction should include counsel to contact the pastor immediately should the infant be in periculo mortis. While we are careful not to cross congregational lines in the discharge of ministerial acts, a true emergency may warrant the securing of the most immediate pastor (e.g., the on-duty hospital chaplain) if the congregational pastor cannot be reached or has not arrived by the time the infant nears articulo mortis (moment of death). The congregational pastor, if unable to respond or in doubt of his/her ability to arrive in time, should immediately arrange for another pastor to respond. The parents should also be instructed on the proper administration of emergency baptism by a lay person so that a parent (or other intimate) might know why to administer it, when to administer it, and how to administer it should a pastor not be available.

Some may object, saying that such a discussion is horribly inappropriate. Given that emergency neo-natal/pediatric CPR is part of the standard childbirth class, how can it be less appropriate to instruct people on emergency lay baptism? Terrible things happen, and infants are fragile. Pre-baptismal instruction should include exposition on the power, effect, benefit, fruit, and purpose of baptism. Baptism is a beautiful and salutary thing. It is a holy ordinance and sacrament. It should be a joy to teach baptism even when what we have to teach touches upon painful, difficult, even frightening subjects. After all, Paul teaches that baptism is about both death and new life. Luther teaches that baptism is completed in death and resurrection. Baptism is about life and death and new life. We should take this to heart.

As this missive is not intended as an exhaustive treatment of baptism per se, I commend to you the many fine things that Luther has written about baptism in The Large Catechism, his treatise, The Holy and Blessed Sacrament of Baptism (1519), and also The Babylonian Captivity of the Church (1520). He sets forth the beauty of the sacrament’s blessings in compelling argument. For those in the mood for a deeper dive into Lutheran dogmatics, might I suggest starting with the relevant chapter in Schmid’s Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. For practical advice on baptism, Gerberding, Marty, and Pfatteicher may prove useful, and, of course, one should read the rubrics in our worship books, keeping in mind that they set forth normative practice for normal circumstances. I include links below for these sources. As always, I am happy to engage in conversation over these matters.

I urge you, clergy and laity, to commend and recommend baptism, especially during these times.

✠Riegel

The Common Service Book (1917), in the general rubrics for baptism, states, “Baptism should be administered at a public Service,” continuing, “When circumstances demand, it may be administered privately, but public announcement thereof shall afterwards be made.” The penultimate general rubric mentions “when at specially appointed Service,” indicating that there could be a service for the purpose of baptizing that we would not consider a regular worship service. Such a service would have been, nonetheless, considered a public service, and it is to be assumed that there would have been announcement of this service the previous Sunday with all invited to attend. This would differentiate it from a private baptism. This rubric continued into The Service Book and Hymnal (1958).

|

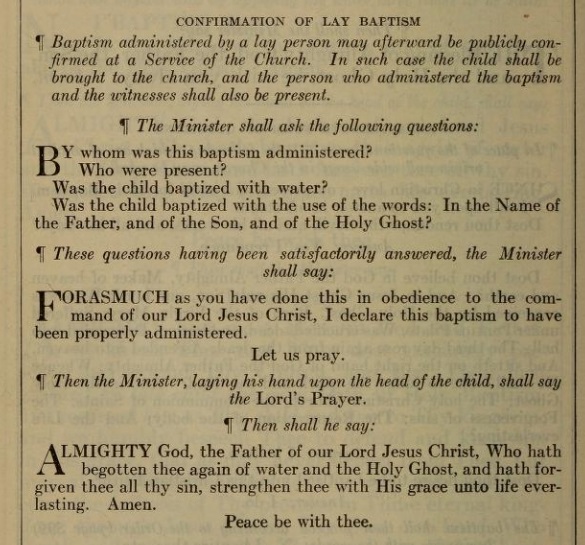

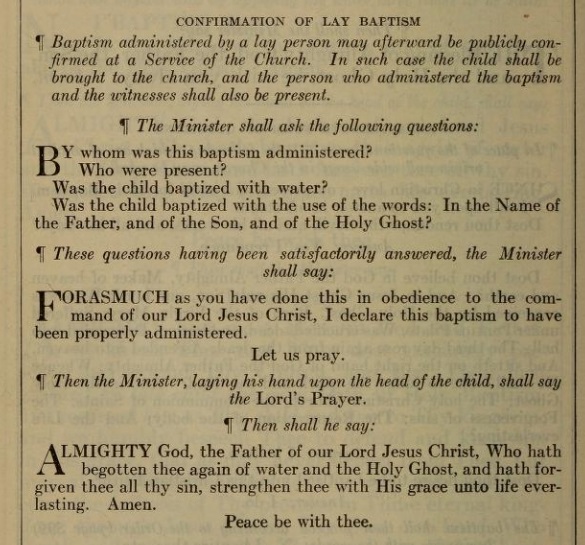

| From the Common Service Book (1919) |

The CSB (1919) included a brief order for emergency baptism by a lay person: “If the child be in extreme illness, and there be no time to call the Minister, any Christian man or woman may administer baptism, being careful to use with the water, the words, N., I baptize thee: In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.” Accompanying this was a short rite of public attestation and confirmation (not to be confused with what we would normally call the Rite of Confirmation) with an interrogation into the employment of the proper material and formal causes of baptism. I am told that this order for both emergency baptism by a lay person and confirmation of the same is found in the minister’s agenda associated with the CSB (1917). That it moved from the minister’s agenda to the pew edition may be a response to the Spanish Flu pandemic. This order for emergency baptism by a lay person (and its accompanying public attestation and confirmation) was retained in The Occasional Services [from the Service Book and Hymnal] (1962), but it was not printed in the SBH (1958) itself. One cannot help but consider this a deficiency. How can the laity administer emergency baptism if they are neither trained to do so nor are given ready access to the form and rubrics?

The Lutheran Book of Worship (1978) makes no reference to emergency baptism, though the Occasional Services (1982) does provide both instructions and a rite. Also included in the OS (1982) is a rite for public recognition, but the interrogation into the material and formal causes of baptism is eliminated.

Of course, if we look at the General Synod’s Book of Worship with Hymns and Tunes (1899), we do not even find a rite for the baptism of children. There is a rite for the baptism of adults, suggesting two possibilities: 1) the rite for baptizing children was considered so simple as to not need participatory material for congregants at a public worship service; or 2) the baptism of children was assumed to be a private affair, despite rubrics to the contrary. Perhaps the Book of Worship with Hymns and Tunes (1899), which was based on an earlier edition, simply lagged behind, from a publishing perspective, evolving thought about baptism in the public worship of the church, evolving thought represented in the minister's agenda that was published at the turn of the century. Anecdotally, we have many accounts, in rural areas, of baptism in the home, and the Lutheran Campus Chapel at WVU has in its possession (what I have been told is) an old traveling baptismal bowl (probably inherited from St. Paul or some other congregation along the way). Then General Synod’s Forms for Ministerial Acts (1900) provides in its general rubrics for baptism, “Baptism should ordinarily be administered at one of the public services of the Church. But if there be a hindrance, it may be administered in private.” It then lays out the same wording as employed in the CSB (1919), concluding the rubric with, “Such baptism must afterwards be reported to the Minister, in order that he may be certified that the sacrament was rightly administered, and that it may be entered on the records of the Church.” There is no rite for public confirmation of an emergency baptism by a lay person as found in the minster’s agenda for the CSB (1917).

As a final note, CSB (1917) includes in the first general rubric for baptism, “Parents are urged not to delay the baptism of their children.” The intent continues into the SBH (1958) second general rubric for baptism with the words, “Infants should be brought to the Church for Holy Baptism as soon as possible after birth.” This injunction is not continued in the LWB (1978), but, in all fairness, general rubrics were not regularly included in the pew edition. One must look to the altar missal (or the Lutheran Book of Worship: Minsters Desk Edition (1978) in which, sadly, all sense of urgency with respect to the baptism of infants is lost.

Formula of Concord, Solid Declaration, Article X – The translation here is from the Concordia Triglotta (1921). This text is in public domain, and my posting it here is in no way a commentary about a preferred translation. You can purchase a Book of Concord (Kolb-Wengert ed., 2000) for a more recent translation. For those interested, the Latin and German texts in the Concordia Triglotta are available online. https://bookofconcord.org/formula-of-concord-solid-declaration/article-x/

Gerberding, G. H.. The Lutheran Pastor (1902) – The section on baptism is found on p. 296. This work is in public domain on the Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/lutheranpastor00gerb/page/296/mode/2up

Schmid, Heinrich. The Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, 3rd ed., revised (1899) – §54 covers baptism, but you may want to read the preceding section that covers sacraments in general as well. https://ccel.org/ccel/schmid/theology/theology.vii.ii.ii.html